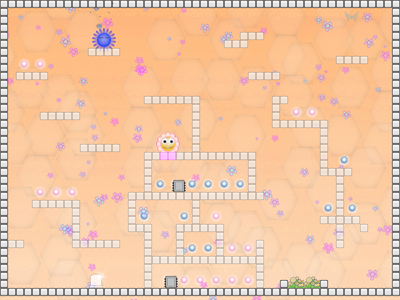

So I have two more working days before I can switch on my out of office autoreply. And on Friday I taught for the last time for a while, as I have been asked to shift role away from front line teaching at least for a time. I probably won't have responsibility for a whole course again until next September/October, and that makes me a little nervous -- I like teaching, and I like students. On Friday, for example, I took a group of students from never having made a functional bit of interactive software before to having built a basic SHMUP. In about three and a half hours. What's not to like about that job?

Shooters have been a little on my mind lately. I am not a big fan (my reflexes are appropriate for my age, as I might politely say to my own parents), but I have seen Pinball Panda confront three in a row in the GMC Cage Match (a Game Maker Community bit of nonsense where members vote on two games in an online poll, with the winner going on to face a new opponent the next week) and I have a feeling that the poor little thing will lose this time (to I Have the Gun, having survived voting against Ever Scrolling Hue and Shoot 2008). A shame, but it has done well for such a casual game, whose core audience is unlikely to be the same demographic as that of the GMC.

Some random numbers: Plays (from all places) 322+8+27=357. Not bad, I feel, although minute by internet standards. Ratings: 2.7/5 (YoYo :(), 8.2/10 (64 Digits :)). Entries in Online Highscore Table: 42. Entries in Online Highscore deleted because of offensive tags: 2. Times Table Hacked: 1.

Ho ho ho, and happy holidays.

Saturday, 20 December 2008

Friday, 12 December 2008

Online Pinball Panda

Pinball Panda continues to be well received, which is nice, and is currently wrestling with Erik Leppen's lovely Shoot 2008 in a Cage Match on the GMC, for those who know about such things. It does suddenly occur to me that it isn't flagged anywhere that the version sitting in the Box.net widget to the right somewhere is offline only, if you want to play the version with online highscores you will need to go to YoYo or 64Digits.

[Edit] I have just uploaded the version with online highscores to the box.net widget. That'll be the zip file rather than an exe. Remember to unzip into one folder and keep the game file in that folder as it uses a DLL to access the magic of the internet.

[Edit] I have just uploaded the version with online highscores to the box.net widget. That'll be the zip file rather than an exe. Remember to unzip into one folder and keep the game file in that folder as it uses a DLL to access the magic of the internet.

Thursday, 4 December 2008

Panda Reviewed

I can't remember now if I was academically interested in User Generated Content before or after I started toying with Game Maker, but I have always seen it as an amateur pursuit that gives me access (and hopefully insight) into something I see as being more and more significant to commercial games. I have played around with Unreal, toyed with machinima, modded NeverWinter Nights (remade as Lilliput just by scaling -- much fun), and recently messed around inside Spore and now Little Big Planet, but I suppose my little experiments with Game Maker have been the closest thing to really making games. At some point I must write the article that all this is supposed to be informing, of course.

But sometimes it is just nice being inside the community. I missed it when it first came out, but there is a lovely little review of Pinball Panda in a community online magazine called GM Weekly (site here, issue with review here. I really like the concluding line: "a perfect casual game". Therefore am I happy. :)

But sometimes it is just nice being inside the community. I missed it when it first came out, but there is a lovely little review of Pinball Panda in a community online magazine called GM Weekly (site here, issue with review here. I really like the concluding line: "a perfect casual game". Therefore am I happy. :)

Friday, 14 November 2008

Revised DiGRA 2009 CFP

Revised Call for Papers

DiGRA 2009

PLEASE NOTE THE NEW DATES FOR SUBMISSION AND DEADLINE FOR REGISTRATION FOR GUARANTEED ON-CAMPUS ACCOMODATION

Breaking New Ground: Innovation in Games, Play, Practice and Theory

Brunel University, West London, United Kingdom, Tuesday 1st September -- Friday 4th September 2009

DiGRA is an organisation that embraces all aspects of game studies, and the conference aims to provide a diverse platform for discussion and a lively forum for debate. We therefore welcome papers from any discipline focused on any aspect of games, play, game culture and industry. The conference will be the fourth DiGRA conference, following Utrecht, Vancouver and Tokyo, and welcomes contributions from scholars working in any area of interest to the association. The official business of the Subject Association will also be conducted at the conference.

The Conference invites the following proposals for consideration:

Individual or Collaborative Papers

Panels

Workshops

Posters

Initial selection will be through the peer review of both full papers and abstracts of 500-700 words in all categories. Selection of presentations will be proportionate to the submissions received, and no distinction will be made between papers selected from abstract or full paper review. Panel and Workshop proposals should include abstracts for the contributions of all participants.

Individual or collaborative papers – addressing topics relevant to the wide remit of DiGRA (including therefore industry, education, political, social, theoretical concerns appropriate to the association). Presentations should be limited to 15-20 mins.

Panel proposals – 3 – 4 papers which address a common theme, a common research method, a shared conceptual issue etc.

Workshops – proposals are invited for 2 – 3 hour workshops that address a range of themes relevant to the aims of the association. Workshops that are particularly targeted at a wide audience are most welcome.

Poster sessions – presentations of work in progress in the format are most welcome and will be showcased throughout the event.

The conference committee are also interested in including featured symposia/colloquia to address particular ‘late-breaking’ research projects or issue-based topics (an example might be a colloquia based around Wii research or a symposium based around Women in Games. Please contact a member of the conference organising committee with any expressions of interest.

Graduate student participation

In order to support graduate students and early career researchers the conference will focus on graduate student issues on its opening day, 1st September 2009. The conference organizers seek appropriate mentors to work with those addressing common themes/topics/issues in graduate roundtables.

Strands

Please also indicate your preference for consideration in one of the following broad strands:

Games Culture

Games and Commerce

Games Aesthetics

Games Education

Games Design

Games and Theory

Key Dates

Deadline for all submissions for presentation at the conference (includes full papers, abstracts and workshop/panel/symposia proposals): Friday 6 March 5pm GMT

Deadline for full papers for inclusion in digital proceedings: Friday 26 June 2009 5pm GMT

Notification of acceptance: June 1 2009

Deadline for booking on-campus accommodation June 30 2009

Conference Dates: 1-4th September 2009

Abstracts should be of 500-700 words and include an indicative bibliography. Full paper submissions may be of up to 6,000 words, not including bibliography. Full details of the submissions procedure, including the method of electronic submission, will be published here and on other forums as soon as possible.

All contributions must be original, unpublished work. The conference language is English, and papers, abstracts and other proposals should be written in English.

Delegates are also advised that individuals will be limited to one paper presentation and one other form of presentation to allow space and time for the largest number of participants.

About the Conference Location

Brunel University is located conveniently near Heathrow Airport and is on the London Tube system. A range of affordable accommodation is available on campus, including 1500 en suite rooms all on one campus, 400 standard bedrooms, 8 holiday flats (5-7 persons per flat), 51 specially adapted rooms for people with disabilities, plus hotel standard rooms in the Lancaster Suite. The Brunel Conference Centre boasts 22 theatres, 29 classrooms and 5 seminar rooms all presented to the highest standard. The following are also available: Free car parking (on application); Full office support for photocopying, faxing, internet and word processing (on application); Comprehensive range of audio visual and media services; Mini market; Pharmacy; Banking facilities; Reference library; Sports Facilities; Fitness Suite; Medical centre; 24 hour security; Self service cafeteria; Licensed bars and cafes. There are also a range of restaurants, cinemas and shopping in Uxbridge town.

Local attractions

Historic Windsor & Eton -Windsor Castle, Legoland and shopping are just 20 minutes drive away London - Central London and West End are easily accessed by bus or Underground. Historic Oxford is a 40 minute bus ride away.

The Conference Organisers

The conference is being hosted by a consortium consisting of Brunel University, University of the West of England and the University of Wales, Newport.

Tanya Krzywinska, Professor of Screen Media, Brunel University

Helen Kennedy, University of the West of England

Barry Atkins, University of Wales Reader in Computer Games Design

DiGRA 2009

PLEASE NOTE THE NEW DATES FOR SUBMISSION AND DEADLINE FOR REGISTRATION FOR GUARANTEED ON-CAMPUS ACCOMODATION

Breaking New Ground: Innovation in Games, Play, Practice and Theory

Brunel University, West London, United Kingdom, Tuesday 1st September -- Friday 4th September 2009

DiGRA is an organisation that embraces all aspects of game studies, and the conference aims to provide a diverse platform for discussion and a lively forum for debate. We therefore welcome papers from any discipline focused on any aspect of games, play, game culture and industry. The conference will be the fourth DiGRA conference, following Utrecht, Vancouver and Tokyo, and welcomes contributions from scholars working in any area of interest to the association. The official business of the Subject Association will also be conducted at the conference.

The Conference invites the following proposals for consideration:

Individual or Collaborative Papers

Panels

Workshops

Posters

Initial selection will be through the peer review of both full papers and abstracts of 500-700 words in all categories. Selection of presentations will be proportionate to the submissions received, and no distinction will be made between papers selected from abstract or full paper review. Panel and Workshop proposals should include abstracts for the contributions of all participants.

Individual or collaborative papers – addressing topics relevant to the wide remit of DiGRA (including therefore industry, education, political, social, theoretical concerns appropriate to the association). Presentations should be limited to 15-20 mins.

Panel proposals – 3 – 4 papers which address a common theme, a common research method, a shared conceptual issue etc.

Workshops – proposals are invited for 2 – 3 hour workshops that address a range of themes relevant to the aims of the association. Workshops that are particularly targeted at a wide audience are most welcome.

Poster sessions – presentations of work in progress in the format are most welcome and will be showcased throughout the event.

The conference committee are also interested in including featured symposia/colloquia to address particular ‘late-breaking’ research projects or issue-based topics (an example might be a colloquia based around Wii research or a symposium based around Women in Games. Please contact a member of the conference organising committee with any expressions of interest.

Graduate student participation

In order to support graduate students and early career researchers the conference will focus on graduate student issues on its opening day, 1st September 2009. The conference organizers seek appropriate mentors to work with those addressing common themes/topics/issues in graduate roundtables.

Strands

Please also indicate your preference for consideration in one of the following broad strands:

Games Culture

Games and Commerce

Games Aesthetics

Games Education

Games Design

Games and Theory

Key Dates

Deadline for all submissions for presentation at the conference (includes full papers, abstracts and workshop/panel/symposia proposals): Friday 6 March 5pm GMT

Deadline for full papers for inclusion in digital proceedings: Friday 26 June 2009 5pm GMT

Notification of acceptance: June 1 2009

Deadline for booking on-campus accommodation June 30 2009

Conference Dates: 1-4th September 2009

Abstracts should be of 500-700 words and include an indicative bibliography. Full paper submissions may be of up to 6,000 words, not including bibliography. Full details of the submissions procedure, including the method of electronic submission, will be published here and on other forums as soon as possible.

All contributions must be original, unpublished work. The conference language is English, and papers, abstracts and other proposals should be written in English.

Delegates are also advised that individuals will be limited to one paper presentation and one other form of presentation to allow space and time for the largest number of participants.

About the Conference Location

Brunel University is located conveniently near Heathrow Airport and is on the London Tube system. A range of affordable accommodation is available on campus, including 1500 en suite rooms all on one campus, 400 standard bedrooms, 8 holiday flats (5-7 persons per flat), 51 specially adapted rooms for people with disabilities, plus hotel standard rooms in the Lancaster Suite. The Brunel Conference Centre boasts 22 theatres, 29 classrooms and 5 seminar rooms all presented to the highest standard. The following are also available: Free car parking (on application); Full office support for photocopying, faxing, internet and word processing (on application); Comprehensive range of audio visual and media services; Mini market; Pharmacy; Banking facilities; Reference library; Sports Facilities; Fitness Suite; Medical centre; 24 hour security; Self service cafeteria; Licensed bars and cafes. There are also a range of restaurants, cinemas and shopping in Uxbridge town.

Local attractions

Historic Windsor & Eton -Windsor Castle, Legoland and shopping are just 20 minutes drive away London - Central London and West End are easily accessed by bus or Underground. Historic Oxford is a 40 minute bus ride away.

The Conference Organisers

The conference is being hosted by a consortium consisting of Brunel University, University of the West of England and the University of Wales, Newport.

Tanya Krzywinska, Professor of Screen Media, Brunel University

Helen Kennedy, University of the West of England

Barry Atkins, University of Wales Reader in Computer Games Design

Wednesday, 12 November 2008

Available Now

So, for anyone who might be interested Pinball Panda now sits in the Box.net widget on the right.

Spent a time today after work playing Left 4 Dead, which was unexpected fun. The premise doesn't grab me half as much as the actual experience. No idea what it would be like long term, and after it comes out of demo, but this was a surprisingly satisfying experience. If I could only now cure my phobi of going online with real people I might even buy the full thing.

And I heart LBP. Even though I like shooting zombies, LBP is the FUTURE I tell you.

Spent a time today after work playing Left 4 Dead, which was unexpected fun. The premise doesn't grab me half as much as the actual experience. No idea what it would be like long term, and after it comes out of demo, but this was a surprisingly satisfying experience. If I could only now cure my phobi of going online with real people I might even buy the full thing.

And I heart LBP. Even though I like shooting zombies, LBP is the FUTURE I tell you.

Tuesday, 4 November 2008

WIP

Monday, 3 November 2008

Radio 4 -- Your Source for all things Videogame

Another astute writer on games, James Newman (go buy Videogames before getting hold of More than a Game and Videogame, Player, Text) has just been speaking about Little Big Planet on Radio 4. I am very impressed, not just by his assured performance, but by Radio 4 (once more) acknowledging the existence of games. On a culture show. It makes me proud to be middle class and British. Although I have my own 'I am working class really' story I am a Radio 4 junkie, which is about as establishment as things get nowadays. Anyway, I was talking to my students only a couple of days ago about the shifting of attitudes towards games as signalled in part by the appearance of what amounted to Nintendo advertisements on ITV and Channel 4 news with Shigeru Miyamoto waving his Wii Music baton about, and this seems to me to be another step towards the normalisation of games in the media. A small step, and a long way to go, but promising.

Hmmm, must make dinner rather than blog, so links to be added later.

Hmmm, must make dinner rather than blog, so links to be added later.

Working things out.

Reading the always astute Steven Poole on "Working for the Man" brought back memories of discussions that followed DiGRA Utrecht where I saw someone (who I will look up) argue in detail that we were all essentially engaged in labour above play. In the spirit of nostalgia gripping me at the moment (was it really that long ago?)I thought I would republish an old old paper of mine here:

“Can I Please Reload From Last Save-Game?”: Getting it Wrong (and Right) in a Nascent Field.

[For some reason this paper generated a lot of response at the time. I would repeat what I have said elsewhere. This is a speaking text of a work in progress. Please regard it as such, and not as a finished article. I am quite proud of the film reference, however.]

Computer game and videogame criticism is a serious business. At the inaugural conference of the Digital Games Research Association (DiGRA) in Utrecht in 2003 there was much public talk of taxonomies and typologies, and of grand theories of definition and categorisation. There was not much talk, however, about why people play games in the first place, and where we find our pleasures in digital games. In one keynote lecture an overarching definition of games was articulated by Jesper Juul that excluded any mention at all of pleasure or fun in its complex diagrammatic representation. Similarly, and in another keynote, Janet Murray asked the assembled students and academics to identify what they considered to be the ‘most significant games’, and not the ones that stuck in the mind of the critic-as-player and player-as-critic as necessarily the most pleasurable. There were no cries of dissent, no revolution on the floor of the auditorium. The audience nodded, satisfied. This is, after all, a serious business, and careers are now at stake. There is a difference between those working in the field, and those who merely enjoy the games. The days of academics commenting on games without ever having played more than a few hours of Myst are more or less over, and we might safely assume that most academic commentators are also players of games, but digital game studies has enough problems getting itself taken seriously without its practitioners giving the game away by talking about just how much fun they might be having. Outside the lecture theatres groups of enthusiasts who also happen to be academics could be heard exchanging anecdotal accounts of pleasures experienced while playing games, but the public rhetoric was all of seriousness and labour.

So much is only to be expected as this nascent field attempts to mark out its boundaries and limits. As Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman note in that most academic of interventions, ‘a footnote to a footnote’, in Rules of Play, there ‘is a tremendous amount of existing research on the philosophical, psychoanalytic, cognitive, and cultural qualities of pleasure’ (330), and it might be too much of a task for any critic to try and produce a synthesis of all extant work in the area into which games might be fitted. It is worth noting, however, just how absent examinations of pleasure have been so far in the burgeoning field of digital game studies, and it might be worth asking ourselves why this might be so, and whether the critical concentration on other issues might have consequences for the development of the field.

In part, of course, any academic engaged in the enterprise of game criticism is only displaying a certain amount of intelligent self-interest in shying away from discussions of pleasure when filling in grant application forms or defending her or his object of study before a still frequently suspicious general public and wider academic community. It might even be convenient, as well as commonplace, to call back to Johan Huizinga’s definition of homo ludens (man the game-player) to substantiate a claim that the playing of games is a constituitive part of our basic humanity, rather than something superfluous or excessive, essential to our selves rather than something we do in our spare time. Games must be more than mere frivolity if we are to justify the labour we are expending on them. In the case of digital games Espen Aarseth, once again, might be considered to have led the way, and his arguments from Cybertext have established a trend in game criticism that few have since questioned. His coinage of the term ‘ergodic’ (from the Greek for ‘work’ and ‘path’) to describe those texts in which ‘nontrivial effort is required to allow the reader to traverse the text’ (1) certainly set up an initial and hugely influential paradigm where the focus is not so much on ‘play’ but on its antonym ‘work’. Inevitably, this has meant that much of the language in which videogames have been discussed has been the language of labour. This is, after all, an industry worth millions, and we are far more likely to see a ‘Serious Games’ initiative than a ‘Non-serious Games’ initiative, and the promise of productivity inherent in ‘Games to Teach’ is more likely to gather industry support than an academic concentration on ‘Games to Play’.

Unfortunately, a side effect of this emphasis on labour might actually prove detrimental to the enterprise in which we are engaged, and move attention away from what should be at the core of what those of us who are cultural critics are concerned with – the identification of what the pleasures of the videogame as an independent artform might be.

What makes games art or what makes games work (in both senses, as efficiently functioning artefacts as well as Aarseth’s textual form necessitating non-trivial effort) seem to be questions that have been taken on board by many of those who would argue that we have a right to our place in academia: what makes games fun. What digital games studies risks if it always deploys a language of labour and work is that it will miss the point somewhat – that players enjoy digital games because they are emphatically not work.

All work and no play makes for a dull videogame

A haggard male figure sits before a keyboard pounding away. The action of striking the keys is mechanical, repetitive, and he has hit a rhythm that looks like it will allow him to continue forever. His concentration is absolute, but his facial expression betrays no pleasure, only a fixed determination to continue to strike the keys. He is ‘in the zone’. He could be playing a game. He could be part of a public information film showing the dangers of single-minded immersion in a videogame. The absolute focus on what he is doing is necessarily exclusive, marking off a distinction between the solitary activity he is engaged in and the social world beyond. He has isolated himself from his family and any kind of society in his monomaniacal compulsion to keep hitting the keys. He is neglecting personal hygiene and the needs of his body, as well as the emotional needs of his family. He explodes with anger when his partner interrupts his communion with the keyboard. But he isn’t playing a game. There is no screen attached to this keyboard. Jack Nicholson is having problems with personal issues in Stanley Kubrik’s film The Shining. He is typing not playing. The manuscript before him grows in size, but we know that this is not the artwork he has come to the Outlook Hotel to write. Page after page of repetition of the single sentence: ‘All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy’.

This reveals much about our understandings of the production of the work of art, and might also shed some light on the way in which videogame play has been positioned in contemporary culture. Jack is not only a ‘dull boy’, but is incapable of the production of the aesthetic object, and will descend into axe-wielding psychosis before long. Endless mechanical repetition will drive you mad, the film declares, and might lead to an explosion of violence. Read as an allegory of contemporary labour where the keyboard is more often the tool of one’s trade than the axe, this offers a stark warning of any repetitive action pursued in the cause of production. The keyboard is not a tool allowing or enabling creativity, it is a machine that binds us to obsessive repetition that strips away our individuality, our humanity and our sanity as surely as the machinery of the production line does.

This, potentially, is what much videogame play looks like from the outside. To the non-gamer (or the non-gaming literate) players of computer games and videogames are pounding away at their keyboards, their gamepads or the button arrays of their GBA SPs and their arcade cabinets. Hands move and eyes dart left and right, but they are chained to the interface. They too are engaged in repetitive mechanical action, in something that looks like the most dehumanising forms of labour, and not in imaginative play. It is no wonder that the rise and rise of the popularity of videogames has made some cultural commentators nervous.

But players of contemporary three-dimensional videogames, with their virtual spaces and ‘narrative architecture’ (Jenkins) open for exploration, are not so immersed in that other world that the playing framework disappears from consciousness and the player is magically transferred through the glass of the screen to somehow position themselves ‘in’ that world. Instead, they are immersed in the experience of playing the game, and something about what is happening on screen compels the player to continue. As the example of Kubrik’s frustrated artist shows so graphically, the worker, too, can be immersed in his task. Whatever Jack’s motive for remaining immersed, however, the game critic should be asking what invites the player to immerse themselves rather than merely noting the possibility of attaining an immersive state, lest the players of games also appear to be driven only by psychosis.[i]

Even critics who enthusiastically embrace videogame play as a form of emergent digital textuality have been sucked into using the metaphor of labour as a way of understanding what it is that players are engaged in during play. Janet Murray makes this point in Hamlet on the Holodeck, where she describes Tetris as

a perfect enactment of the overtasked lives of Americans in the 1990s --- of the constant bombardment of tasks that demand our attention and that we must somehow fit into our overcrowded schedules and clear off our desks in order to make room for the next onslaught. (144)

Of course, such a characterisation of the action of videogame play invites a misunderstanding of what can be seen from the outside (the physical action or enactment of play) over the experience of playing games that keeps gamers playing (the management and manipulation of the constantly changing image on the screen). Gamers are not, and never have been, engaged in simply repetitive physical action. We do not clear our screens only to have exactly the same task arrive to replace the one so recently disposed of. For all the observations that some games feel like work, particularly in their resemblance to the domestic labour of ‘tidying up’, games that demand truly repetitive mechanical action quickly fall into tedium. What Murray does not emphasise enough, perhaps, is the way in which Tetris never falls into the tedium of work on the production line, that most feared form of labour where there should be no deviation from the repetitive task before the worker and no form of independent agency is permitted. Where Tetris hooks its player is in its shifting of the exact nature of the task before us. It does so in an obvious and straightforward way, with its incremental increase in the speed of the falling blocks, but in each individual playing of Tetris we also always have a new challenge before us, never a straightforward repetition of the task just completed. If this were simply an enactment of the production line, whether in its traditional incarnation in the factory or in the white-collar manifestation that Murray alludes to, then it would fail as a game that we play for pleasure. Conversely, if our experience of work is comparable to that of Tetris, with its ever increasing difficulty ratcheting up towards an inevitable ending at which we will fail and must fail, than we should seriously consider a career change.

For all that games might reflect our working practices and, at least in the case of games played on the Mac and PC might actually occupy the same physical space as our labour, they are not simply versions of labour tasks that we have somehow been hoodwinked into mistaking for fun. If we are to think in terms of games as a series of tasks performed, then we need to recognise that they do not, in the main, rely on repetition (the monotony of a closed loop) but on iteration (essentially repetition always with difference). All work and no play makes for a dull and unsatisfying videogame, or, all repetition and no iteration makes for something which, as labour, hardly qualifies for consideration in terms of its aesthetics. This distinction is sometimes missed, however, when the pleasures of games are articulated, as in this article in the British games magazine Edge:

Then there’s the therapy of it all: returning to a repetitive game is a lot like alphabetising your CD collection. Remedial manual labour that allows your brain to have a cigar and a nice long bath. And, finally, there’s the necessary relaxation on behalf of the player. You’ve got to be able to let go and just cha-cha-cha with the one note rhythm. Put your brain into freefall, and let the gravity of a choice-free system do the work for you. (95)

Of course, this is an inversion of Murray’s formulation in its celebration of the relaxation that such games afford that still relies on the antonymic relationship of game to labour. The videogames referred to here, primarily rhythm-action games, on-rails shooters and side-scrolling games, provide respite from the whirring complexities of the Edge journalist’s daily grind. It might resemble one form of (manual) labour, but it is played because it is anything but a re-enactment of the professional labour of the writer. It is in the action of play as it is understood in the imagination of the player and not in the movement of the body that we might locate a key specificity of videogame aesthetics.

This dependence on iteration is even more evident in the more sophisticated games that have been produced as the technology available to games developers has advanced by leaps and bounds, especially in terms of speed of processing and data storage. The complex contemporary videogame role-playing game, third-person adventure or first-person shooter, in particular, are essentially iterative forms because they are designed to be played with, rather than simply worked at – that is, their aesthetic relies on repetition with difference within the governance of rules, and one of their core pleasures is located not in textual mastery, but in the iterative experience of the textual fragment allowed through play. In their huge virtual spaces, exponentially increasing levels of detail and sometimes convoluted emplotments such games are full of excess and redundancy, of experiences that can be accessed but need not necessarily be accessed in order to progress to a moment of victory over the game. This then sees the videogame caught in something of a double-bind, as one of the most significantly distinctive aesthetic characteristics of such computer games and videogames (that they do require ‘non-trivial effort’, that the range of tasks that must be undertaken to unlock all the experiences offered by a game is always increasing) is at least in part responsible for the location of videogaming outside the discourses of aesthetic criticism, at least by those who look in on gaming from the outside.

Kill the Boss

As you read these words thousands of workers in offices around the world are playing games on the machines provided to enable or increase their productivity. If they are careful they may well look as if they are working when they are actually playing. They might even, with their rapt attention focused on the screen and their controlled movements of the mouse and their deliberate taps on the keyboard, look like model employees. It all depends, or might depend, on whether the employer sees the player or the screen. Despite the best efforts of commercial IT departments, with their ever-increasing function of surveillance, workers are playing Solitaire, Hearts or Minesweeper in Windows. Virtual silver balls are bouncing around virtual Pinball tables in Auckland and Calgary, Manchester and New York, Rome and Budapest. Some of the more adventurous workers will be playing the latest Flash game accessed through the internet, or even engaging in a little LAN deathmatch with co-workers. Computing professionals might still claim that a multiplayer game of Quake played across their organisation’s machines is an essential part of their job that tests whether the system is robust, but most such play is marginally subversive, a transgression of sorts, and even an offence that might lead to disciplinary action if discovered. In my own workplace even access to the games that come free with Windows has been blocked. My employers have a clear sense that there is a distinction between work and play. And computer games are certainly not defined as work.

If the computer game is a form of leisure that is best understood through a comparison with contemporary working practices, then it offers a model of work that many of us can only aspire to and hope for. A lucky few have achieved a position in their working lives where they may dawdle and choose the tasks they wish to attend to, where they can make mistakes without any more consequence than deciding whether they want to attempt the same task again, where they can walk away and do something different if a task becomes tiresome, and where their personnel files are of as much significance as the save-game files on our memory cards or hard-drives. Chris Crawford has written about games as providing a place of ‘safety’ (quoted in Juul 31) where the consequences of a simulation are always less extreme than they would be in the world of lived experience, and he is absolutely right. There are always imperatives in games if they are understood as tyrannies that demand that I complete them, but my relationship with the games that I play is very different from the relationship I have with my institutional employer. The game may demand that I progress, advance and complete it. But there is no exterior imperative. I will not be fired if I just walk away from the unreasonable demands of a game that asks me to do anything that I do not enjoy, that gives me no pleasure. I enter into a contract which I suppose will mean that the product of my labour, my wages converted into a plastic DVD box and a silver disk, will provide me with something other than more labour. I am a consumer of the many and varied pleasures of games, and not a producer of game endings bound to follow the imperatives set out by the game’s developers. I can refuse the demands a game makes of me in a way that might make me much more nervous if I was refusing the demands of my line-manager.

It is even possible to see such games either positively or negatively as a form of leisure practice that is necessarily antithetical to work. This might be expressed in the liberating terms of allowing an exercise of individual agency that is missing from Murray’s characterisation of the lives of American workers (I am doing this because I choose to, and not because I must). Alternatively we might see them in a more negative light as something like a contemporary technological invitation to something like Theodor Adorno’s ‘false consciousness’ in allowing an illusory release from the demands of conformity made in so many commercial workplaces that acts as a safety valve that stops us rebelling against the organisations that crush and dehumanise us. However we view the games that we play and study, and however we dicuss them, we must remain aware that they are games that players choose to play, and that the motivation behind that choice is important.

It is more than mere accident that the adversaries who must be overcome in many kinds of videogame are commonly referred to as ‘bosses’. That the videogame often invites, and even necessitates, confrontation with bosses, and those bosses can and must be defeated emphasises the way in which the games stand in clear opposition to our daily labour. David Kushner’s entertaining Masters of Doom traces a familiar narrative arc in its account of the rise and subsequent fall of the founders of id Software, John Carmack and John Romero. It was the trappings of economic success and the seduction of the business the games became, according to Kushner, that saw the makers of Doom doomed. Great games, he tells us, were spawned when maverick outsiders ‘borrowed’ their employers’ computers and decamped to lakeside houses. Offices spawn the likes of Daikatana: Doom was a fan’s game, a maverick’s game. Kushner also includes a fascinating anecdote in which Romero discovers an Easter Egg left in the final boss encounter of Doom II by some of his programming team (180). Positioned behind the boss in a hidden room was a representation of Romero’s own head. A round that hits the final boss in the head, the difficult task that must be repeated if the player is to complete the game, would also hit their employer. In order to defeat the boss, at least for the team at id, one would have to kill the boss, a reminder that this remains a playful practice that is antithetical to labour and even threatens a minor and local subversion of the usual hierarchies of labour as workers attempt to exercise individual agency.

Of course computer game and videogame play often resembles work, just as much as other forms of play resemble other forms of labour, whether we are playing doctors and nurses, the three year old is knocking pegs into holes with a plastic hammer, or we are commanding an army made of sixteen finely crafted ivory pieces. But the player is still playing, and not working in any meaningful sense. Games are not only mobilized by progression down the line, the completion of tasks with robotic efficiency, or the production of endings in a drive to completion.

“Can I Please Reload From Last Save-Game?”: Getting it Wrong (and Right) in a Nascent Field.

[For some reason this paper generated a lot of response at the time. I would repeat what I have said elsewhere. This is a speaking text of a work in progress. Please regard it as such, and not as a finished article. I am quite proud of the film reference, however.]

Computer game and videogame criticism is a serious business. At the inaugural conference of the Digital Games Research Association (DiGRA) in Utrecht in 2003 there was much public talk of taxonomies and typologies, and of grand theories of definition and categorisation. There was not much talk, however, about why people play games in the first place, and where we find our pleasures in digital games. In one keynote lecture an overarching definition of games was articulated by Jesper Juul that excluded any mention at all of pleasure or fun in its complex diagrammatic representation. Similarly, and in another keynote, Janet Murray asked the assembled students and academics to identify what they considered to be the ‘most significant games’, and not the ones that stuck in the mind of the critic-as-player and player-as-critic as necessarily the most pleasurable. There were no cries of dissent, no revolution on the floor of the auditorium. The audience nodded, satisfied. This is, after all, a serious business, and careers are now at stake. There is a difference between those working in the field, and those who merely enjoy the games. The days of academics commenting on games without ever having played more than a few hours of Myst are more or less over, and we might safely assume that most academic commentators are also players of games, but digital game studies has enough problems getting itself taken seriously without its practitioners giving the game away by talking about just how much fun they might be having. Outside the lecture theatres groups of enthusiasts who also happen to be academics could be heard exchanging anecdotal accounts of pleasures experienced while playing games, but the public rhetoric was all of seriousness and labour.

So much is only to be expected as this nascent field attempts to mark out its boundaries and limits. As Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman note in that most academic of interventions, ‘a footnote to a footnote’, in Rules of Play, there ‘is a tremendous amount of existing research on the philosophical, psychoanalytic, cognitive, and cultural qualities of pleasure’ (330), and it might be too much of a task for any critic to try and produce a synthesis of all extant work in the area into which games might be fitted. It is worth noting, however, just how absent examinations of pleasure have been so far in the burgeoning field of digital game studies, and it might be worth asking ourselves why this might be so, and whether the critical concentration on other issues might have consequences for the development of the field.

In part, of course, any academic engaged in the enterprise of game criticism is only displaying a certain amount of intelligent self-interest in shying away from discussions of pleasure when filling in grant application forms or defending her or his object of study before a still frequently suspicious general public and wider academic community. It might even be convenient, as well as commonplace, to call back to Johan Huizinga’s definition of homo ludens (man the game-player) to substantiate a claim that the playing of games is a constituitive part of our basic humanity, rather than something superfluous or excessive, essential to our selves rather than something we do in our spare time. Games must be more than mere frivolity if we are to justify the labour we are expending on them. In the case of digital games Espen Aarseth, once again, might be considered to have led the way, and his arguments from Cybertext have established a trend in game criticism that few have since questioned. His coinage of the term ‘ergodic’ (from the Greek for ‘work’ and ‘path’) to describe those texts in which ‘nontrivial effort is required to allow the reader to traverse the text’ (1) certainly set up an initial and hugely influential paradigm where the focus is not so much on ‘play’ but on its antonym ‘work’. Inevitably, this has meant that much of the language in which videogames have been discussed has been the language of labour. This is, after all, an industry worth millions, and we are far more likely to see a ‘Serious Games’ initiative than a ‘Non-serious Games’ initiative, and the promise of productivity inherent in ‘Games to Teach’ is more likely to gather industry support than an academic concentration on ‘Games to Play’.

Unfortunately, a side effect of this emphasis on labour might actually prove detrimental to the enterprise in which we are engaged, and move attention away from what should be at the core of what those of us who are cultural critics are concerned with – the identification of what the pleasures of the videogame as an independent artform might be.

What makes games art or what makes games work (in both senses, as efficiently functioning artefacts as well as Aarseth’s textual form necessitating non-trivial effort) seem to be questions that have been taken on board by many of those who would argue that we have a right to our place in academia: what makes games fun. What digital games studies risks if it always deploys a language of labour and work is that it will miss the point somewhat – that players enjoy digital games because they are emphatically not work.

All work and no play makes for a dull videogame

A haggard male figure sits before a keyboard pounding away. The action of striking the keys is mechanical, repetitive, and he has hit a rhythm that looks like it will allow him to continue forever. His concentration is absolute, but his facial expression betrays no pleasure, only a fixed determination to continue to strike the keys. He is ‘in the zone’. He could be playing a game. He could be part of a public information film showing the dangers of single-minded immersion in a videogame. The absolute focus on what he is doing is necessarily exclusive, marking off a distinction between the solitary activity he is engaged in and the social world beyond. He has isolated himself from his family and any kind of society in his monomaniacal compulsion to keep hitting the keys. He is neglecting personal hygiene and the needs of his body, as well as the emotional needs of his family. He explodes with anger when his partner interrupts his communion with the keyboard. But he isn’t playing a game. There is no screen attached to this keyboard. Jack Nicholson is having problems with personal issues in Stanley Kubrik’s film The Shining. He is typing not playing. The manuscript before him grows in size, but we know that this is not the artwork he has come to the Outlook Hotel to write. Page after page of repetition of the single sentence: ‘All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy’.

This reveals much about our understandings of the production of the work of art, and might also shed some light on the way in which videogame play has been positioned in contemporary culture. Jack is not only a ‘dull boy’, but is incapable of the production of the aesthetic object, and will descend into axe-wielding psychosis before long. Endless mechanical repetition will drive you mad, the film declares, and might lead to an explosion of violence. Read as an allegory of contemporary labour where the keyboard is more often the tool of one’s trade than the axe, this offers a stark warning of any repetitive action pursued in the cause of production. The keyboard is not a tool allowing or enabling creativity, it is a machine that binds us to obsessive repetition that strips away our individuality, our humanity and our sanity as surely as the machinery of the production line does.

This, potentially, is what much videogame play looks like from the outside. To the non-gamer (or the non-gaming literate) players of computer games and videogames are pounding away at their keyboards, their gamepads or the button arrays of their GBA SPs and their arcade cabinets. Hands move and eyes dart left and right, but they are chained to the interface. They too are engaged in repetitive mechanical action, in something that looks like the most dehumanising forms of labour, and not in imaginative play. It is no wonder that the rise and rise of the popularity of videogames has made some cultural commentators nervous.

But players of contemporary three-dimensional videogames, with their virtual spaces and ‘narrative architecture’ (Jenkins) open for exploration, are not so immersed in that other world that the playing framework disappears from consciousness and the player is magically transferred through the glass of the screen to somehow position themselves ‘in’ that world. Instead, they are immersed in the experience of playing the game, and something about what is happening on screen compels the player to continue. As the example of Kubrik’s frustrated artist shows so graphically, the worker, too, can be immersed in his task. Whatever Jack’s motive for remaining immersed, however, the game critic should be asking what invites the player to immerse themselves rather than merely noting the possibility of attaining an immersive state, lest the players of games also appear to be driven only by psychosis.[i]

Even critics who enthusiastically embrace videogame play as a form of emergent digital textuality have been sucked into using the metaphor of labour as a way of understanding what it is that players are engaged in during play. Janet Murray makes this point in Hamlet on the Holodeck, where she describes Tetris as

a perfect enactment of the overtasked lives of Americans in the 1990s --- of the constant bombardment of tasks that demand our attention and that we must somehow fit into our overcrowded schedules and clear off our desks in order to make room for the next onslaught. (144)

Of course, such a characterisation of the action of videogame play invites a misunderstanding of what can be seen from the outside (the physical action or enactment of play) over the experience of playing games that keeps gamers playing (the management and manipulation of the constantly changing image on the screen). Gamers are not, and never have been, engaged in simply repetitive physical action. We do not clear our screens only to have exactly the same task arrive to replace the one so recently disposed of. For all the observations that some games feel like work, particularly in their resemblance to the domestic labour of ‘tidying up’, games that demand truly repetitive mechanical action quickly fall into tedium. What Murray does not emphasise enough, perhaps, is the way in which Tetris never falls into the tedium of work on the production line, that most feared form of labour where there should be no deviation from the repetitive task before the worker and no form of independent agency is permitted. Where Tetris hooks its player is in its shifting of the exact nature of the task before us. It does so in an obvious and straightforward way, with its incremental increase in the speed of the falling blocks, but in each individual playing of Tetris we also always have a new challenge before us, never a straightforward repetition of the task just completed. If this were simply an enactment of the production line, whether in its traditional incarnation in the factory or in the white-collar manifestation that Murray alludes to, then it would fail as a game that we play for pleasure. Conversely, if our experience of work is comparable to that of Tetris, with its ever increasing difficulty ratcheting up towards an inevitable ending at which we will fail and must fail, than we should seriously consider a career change.

For all that games might reflect our working practices and, at least in the case of games played on the Mac and PC might actually occupy the same physical space as our labour, they are not simply versions of labour tasks that we have somehow been hoodwinked into mistaking for fun. If we are to think in terms of games as a series of tasks performed, then we need to recognise that they do not, in the main, rely on repetition (the monotony of a closed loop) but on iteration (essentially repetition always with difference). All work and no play makes for a dull and unsatisfying videogame, or, all repetition and no iteration makes for something which, as labour, hardly qualifies for consideration in terms of its aesthetics. This distinction is sometimes missed, however, when the pleasures of games are articulated, as in this article in the British games magazine Edge:

Then there’s the therapy of it all: returning to a repetitive game is a lot like alphabetising your CD collection. Remedial manual labour that allows your brain to have a cigar and a nice long bath. And, finally, there’s the necessary relaxation on behalf of the player. You’ve got to be able to let go and just cha-cha-cha with the one note rhythm. Put your brain into freefall, and let the gravity of a choice-free system do the work for you. (95)

Of course, this is an inversion of Murray’s formulation in its celebration of the relaxation that such games afford that still relies on the antonymic relationship of game to labour. The videogames referred to here, primarily rhythm-action games, on-rails shooters and side-scrolling games, provide respite from the whirring complexities of the Edge journalist’s daily grind. It might resemble one form of (manual) labour, but it is played because it is anything but a re-enactment of the professional labour of the writer. It is in the action of play as it is understood in the imagination of the player and not in the movement of the body that we might locate a key specificity of videogame aesthetics.

This dependence on iteration is even more evident in the more sophisticated games that have been produced as the technology available to games developers has advanced by leaps and bounds, especially in terms of speed of processing and data storage. The complex contemporary videogame role-playing game, third-person adventure or first-person shooter, in particular, are essentially iterative forms because they are designed to be played with, rather than simply worked at – that is, their aesthetic relies on repetition with difference within the governance of rules, and one of their core pleasures is located not in textual mastery, but in the iterative experience of the textual fragment allowed through play. In their huge virtual spaces, exponentially increasing levels of detail and sometimes convoluted emplotments such games are full of excess and redundancy, of experiences that can be accessed but need not necessarily be accessed in order to progress to a moment of victory over the game. This then sees the videogame caught in something of a double-bind, as one of the most significantly distinctive aesthetic characteristics of such computer games and videogames (that they do require ‘non-trivial effort’, that the range of tasks that must be undertaken to unlock all the experiences offered by a game is always increasing) is at least in part responsible for the location of videogaming outside the discourses of aesthetic criticism, at least by those who look in on gaming from the outside.

Kill the Boss

As you read these words thousands of workers in offices around the world are playing games on the machines provided to enable or increase their productivity. If they are careful they may well look as if they are working when they are actually playing. They might even, with their rapt attention focused on the screen and their controlled movements of the mouse and their deliberate taps on the keyboard, look like model employees. It all depends, or might depend, on whether the employer sees the player or the screen. Despite the best efforts of commercial IT departments, with their ever-increasing function of surveillance, workers are playing Solitaire, Hearts or Minesweeper in Windows. Virtual silver balls are bouncing around virtual Pinball tables in Auckland and Calgary, Manchester and New York, Rome and Budapest. Some of the more adventurous workers will be playing the latest Flash game accessed through the internet, or even engaging in a little LAN deathmatch with co-workers. Computing professionals might still claim that a multiplayer game of Quake played across their organisation’s machines is an essential part of their job that tests whether the system is robust, but most such play is marginally subversive, a transgression of sorts, and even an offence that might lead to disciplinary action if discovered. In my own workplace even access to the games that come free with Windows has been blocked. My employers have a clear sense that there is a distinction between work and play. And computer games are certainly not defined as work.

If the computer game is a form of leisure that is best understood through a comparison with contemporary working practices, then it offers a model of work that many of us can only aspire to and hope for. A lucky few have achieved a position in their working lives where they may dawdle and choose the tasks they wish to attend to, where they can make mistakes without any more consequence than deciding whether they want to attempt the same task again, where they can walk away and do something different if a task becomes tiresome, and where their personnel files are of as much significance as the save-game files on our memory cards or hard-drives. Chris Crawford has written about games as providing a place of ‘safety’ (quoted in Juul 31) where the consequences of a simulation are always less extreme than they would be in the world of lived experience, and he is absolutely right. There are always imperatives in games if they are understood as tyrannies that demand that I complete them, but my relationship with the games that I play is very different from the relationship I have with my institutional employer. The game may demand that I progress, advance and complete it. But there is no exterior imperative. I will not be fired if I just walk away from the unreasonable demands of a game that asks me to do anything that I do not enjoy, that gives me no pleasure. I enter into a contract which I suppose will mean that the product of my labour, my wages converted into a plastic DVD box and a silver disk, will provide me with something other than more labour. I am a consumer of the many and varied pleasures of games, and not a producer of game endings bound to follow the imperatives set out by the game’s developers. I can refuse the demands a game makes of me in a way that might make me much more nervous if I was refusing the demands of my line-manager.

It is even possible to see such games either positively or negatively as a form of leisure practice that is necessarily antithetical to work. This might be expressed in the liberating terms of allowing an exercise of individual agency that is missing from Murray’s characterisation of the lives of American workers (I am doing this because I choose to, and not because I must). Alternatively we might see them in a more negative light as something like a contemporary technological invitation to something like Theodor Adorno’s ‘false consciousness’ in allowing an illusory release from the demands of conformity made in so many commercial workplaces that acts as a safety valve that stops us rebelling against the organisations that crush and dehumanise us. However we view the games that we play and study, and however we dicuss them, we must remain aware that they are games that players choose to play, and that the motivation behind that choice is important.

It is more than mere accident that the adversaries who must be overcome in many kinds of videogame are commonly referred to as ‘bosses’. That the videogame often invites, and even necessitates, confrontation with bosses, and those bosses can and must be defeated emphasises the way in which the games stand in clear opposition to our daily labour. David Kushner’s entertaining Masters of Doom traces a familiar narrative arc in its account of the rise and subsequent fall of the founders of id Software, John Carmack and John Romero. It was the trappings of economic success and the seduction of the business the games became, according to Kushner, that saw the makers of Doom doomed. Great games, he tells us, were spawned when maverick outsiders ‘borrowed’ their employers’ computers and decamped to lakeside houses. Offices spawn the likes of Daikatana: Doom was a fan’s game, a maverick’s game. Kushner also includes a fascinating anecdote in which Romero discovers an Easter Egg left in the final boss encounter of Doom II by some of his programming team (180). Positioned behind the boss in a hidden room was a representation of Romero’s own head. A round that hits the final boss in the head, the difficult task that must be repeated if the player is to complete the game, would also hit their employer. In order to defeat the boss, at least for the team at id, one would have to kill the boss, a reminder that this remains a playful practice that is antithetical to labour and even threatens a minor and local subversion of the usual hierarchies of labour as workers attempt to exercise individual agency.

Of course computer game and videogame play often resembles work, just as much as other forms of play resemble other forms of labour, whether we are playing doctors and nurses, the three year old is knocking pegs into holes with a plastic hammer, or we are commanding an army made of sixteen finely crafted ivory pieces. But the player is still playing, and not working in any meaningful sense. Games are not only mobilized by progression down the line, the completion of tasks with robotic efficiency, or the production of endings in a drive to completion.

Tuesday, 30 September 2008

What I did today apart from play WipEout HD

First Call for Papers

DiGRA 2009

Breaking New Ground: Innovation in Games, Play, Practice and Theory

Brunel University, West London, United Kingdom, Tuesday 1st September -- Friday 4th September 2009

The South of Britain Consortium are pleased to announce the first Call for Papers for the Digital Games Research Association 2009. DiGRA is an organisation that embraces all aspects of game studies, and the conference aims to provide a diverse platform for discussion, and a lively forum for debate. We therefore welcome papers from any discipline focused on any aspect of games, play, game culture and the games industry. The conference will be the fourth DiGRA conference, following Utrecht, Vancouver and Tokyo, and welcomes contributions from scholars working in any area of interest to the association. The official business of the Subject Association will also be conducted at the conference.

The Conference invites the following proposals for consideration:

Individual or Collaborative Papers

Panels

Workshops

Posters

Graduate Student Roundtable Papers

Initial selection will be through the peer review of abstracts of 500-700 words in all categories. Panel and Workshop proposals should include abstracts for the contributions of all participants.

Individual or collaborative papers – addressing topics relevant to the wide remit of DiGRA (including therefore industry, education, political, social, theoretical concerns appropriate to the association). Presentations should be limited to 15-20 mins.

Panel proposals – 3 – 4 papers which address a common theme, a common research method, a shared conceptual issue etc.

Workshops – proposals are invited for 2 – 3 hour workshops that address a range of themes relevant to the aims of the association. Workshops that are particularly targeted at a wide audience are most welcome.

Poster sessions – presentations of work in progress in the format are most welcome and will be showcased throughout the event.

The conference committee are also interested in including featured symposia/colloquia to address particular ‘late-breaking’ research projects or issue-based topics (an example might be a colloquia based around Wii research or a symposium based around Women in Games). Please contact a member of the conference organising committee with any expressions of interest.

Graduate student participation

In order to support graduate students and early career researchers the conference will focus on graduate student issues on its opening day, 1st September 2009. We therefore ask for volunteers for mentoring sessions from established academics. For those graduate students whose research is at an early stage, and who wish to work with mentors, we invite work in progress proposals for presentations at mentor roundtables. Such roundtable participation, however, should in no way be seen as preventing graduate students putting in abstracts for other forms of participation.

Strands

Please also indicate your preference for consideration in one of the following broad strands:

Games Culture

Games and Commerce

Games Aesthetics

Games Technology

Games Education

Games Design

Games and Public Policy

Games and Theory

Key Dates

Deadline for all abstracts and workshop/panel/symposia proposals: Friday 17 April 5pm GMT

Deadline for full papers for inclusion in digital proceedings: Friday 26 June 2009 5pm GMT

Notification of abstract acceptance: June 1 2009

Conference Dates: 1-4th September 2009

Abstracts should be of 500-700 words and include an additional indicative bibliography. Full paper submissions may be of up to 6,000 words. Full details of the submissions procedure, including the method of electronic submission, will be published here and on other forums as soon as possible.

All contributions must be original, unpublished work. The conference language is English, and papers, abstracts and other proposals should be written in English.

Delegates are also advised that individuals will be limited to one paper presentation and one other form of presentation to allow space and time for the largest number of participants.

About the Conference Location

Brunel University is located conveniently near Heathrow Airport and is on the London Tube system. A range of affordable accommodation is available on campus, including 1500 en suite rooms all on one campus, 400 standard bedrooms, 8 holiday flats (5-7 persons per flat), 51 specially adapted rooms for people with disabilities, plus hotel standard rooms in the Lancaster Suite. The Brunel Conference Centre boasts 22 theatres, 29 classrooms and 5 seminar rooms all presented to the highest standard. The following are also available: Free car parking (on application); Full office support for photocopying, faxing, internet and word processing (on application); Comprehensive range of audio visual and media services; Mini market; Pharmacy; Banking facilities; Reference library; Sports Facilities; Fitness Suite; Medical centre; 24 hour security; Self service cafeteria; Licensed bars and cafes. There are also a range of restaurants, cinemas and shopping in Uxbridge town.

Local attractions

Historic Windsor & Eton -Windsor Castle, Legoland and shopping are just 20 minutes drive away London - Central London and West End are easily accessed by bus or Underground. Historic Oxford is a 40 minute bus ride away.

The Conference Organisers

The conference is being hosted by a consortium consisting of Brunel University, University of the West of England, and the University of Wales, Newport.

Tanya Krzywinska, Professor of Screen Media, Brunel University. Tanya.Krzywinska@brunel.ac.uk

Helen Kennedy, Chair of the Play Research Group, University of the West of England. helen.kennedy@uwe.ac.uk

Barry Atkins, University of Wales Reader in Computer Games Design, University of Wales, Newport. barry.atkins@newport.ac.uk

DiGRA 2009

Breaking New Ground: Innovation in Games, Play, Practice and Theory

Brunel University, West London, United Kingdom, Tuesday 1st September -- Friday 4th September 2009

The South of Britain Consortium are pleased to announce the first Call for Papers for the Digital Games Research Association 2009. DiGRA is an organisation that embraces all aspects of game studies, and the conference aims to provide a diverse platform for discussion, and a lively forum for debate. We therefore welcome papers from any discipline focused on any aspect of games, play, game culture and the games industry. The conference will be the fourth DiGRA conference, following Utrecht, Vancouver and Tokyo, and welcomes contributions from scholars working in any area of interest to the association. The official business of the Subject Association will also be conducted at the conference.

The Conference invites the following proposals for consideration:

Individual or Collaborative Papers

Panels

Workshops

Posters

Graduate Student Roundtable Papers

Initial selection will be through the peer review of abstracts of 500-700 words in all categories. Panel and Workshop proposals should include abstracts for the contributions of all participants.

Individual or collaborative papers – addressing topics relevant to the wide remit of DiGRA (including therefore industry, education, political, social, theoretical concerns appropriate to the association). Presentations should be limited to 15-20 mins.

Panel proposals – 3 – 4 papers which address a common theme, a common research method, a shared conceptual issue etc.

Workshops – proposals are invited for 2 – 3 hour workshops that address a range of themes relevant to the aims of the association. Workshops that are particularly targeted at a wide audience are most welcome.

Poster sessions – presentations of work in progress in the format are most welcome and will be showcased throughout the event.

The conference committee are also interested in including featured symposia/colloquia to address particular ‘late-breaking’ research projects or issue-based topics (an example might be a colloquia based around Wii research or a symposium based around Women in Games). Please contact a member of the conference organising committee with any expressions of interest.

Graduate student participation

In order to support graduate students and early career researchers the conference will focus on graduate student issues on its opening day, 1st September 2009. We therefore ask for volunteers for mentoring sessions from established academics. For those graduate students whose research is at an early stage, and who wish to work with mentors, we invite work in progress proposals for presentations at mentor roundtables. Such roundtable participation, however, should in no way be seen as preventing graduate students putting in abstracts for other forms of participation.

Strands

Please also indicate your preference for consideration in one of the following broad strands:

Games Culture

Games and Commerce

Games Aesthetics

Games Technology

Games Education

Games Design

Games and Public Policy

Games and Theory

Key Dates

Deadline for all abstracts and workshop/panel/symposia proposals: Friday 17 April 5pm GMT

Deadline for full papers for inclusion in digital proceedings: Friday 26 June 2009 5pm GMT

Notification of abstract acceptance: June 1 2009

Conference Dates: 1-4th September 2009

Abstracts should be of 500-700 words and include an additional indicative bibliography. Full paper submissions may be of up to 6,000 words. Full details of the submissions procedure, including the method of electronic submission, will be published here and on other forums as soon as possible.

All contributions must be original, unpublished work. The conference language is English, and papers, abstracts and other proposals should be written in English.

Delegates are also advised that individuals will be limited to one paper presentation and one other form of presentation to allow space and time for the largest number of participants.

About the Conference Location

Brunel University is located conveniently near Heathrow Airport and is on the London Tube system. A range of affordable accommodation is available on campus, including 1500 en suite rooms all on one campus, 400 standard bedrooms, 8 holiday flats (5-7 persons per flat), 51 specially adapted rooms for people with disabilities, plus hotel standard rooms in the Lancaster Suite. The Brunel Conference Centre boasts 22 theatres, 29 classrooms and 5 seminar rooms all presented to the highest standard. The following are also available: Free car parking (on application); Full office support for photocopying, faxing, internet and word processing (on application); Comprehensive range of audio visual and media services; Mini market; Pharmacy; Banking facilities; Reference library; Sports Facilities; Fitness Suite; Medical centre; 24 hour security; Self service cafeteria; Licensed bars and cafes. There are also a range of restaurants, cinemas and shopping in Uxbridge town.

Local attractions

Historic Windsor & Eton -Windsor Castle, Legoland and shopping are just 20 minutes drive away London - Central London and West End are easily accessed by bus or Underground. Historic Oxford is a 40 minute bus ride away.

The Conference Organisers

The conference is being hosted by a consortium consisting of Brunel University, University of the West of England, and the University of Wales, Newport.

Tanya Krzywinska, Professor of Screen Media, Brunel University. Tanya.Krzywinska@brunel.ac.uk

Helen Kennedy, Chair of the Play Research Group, University of the West of England. helen.kennedy@uwe.ac.uk

Barry Atkins, University of Wales Reader in Computer Games Design, University of Wales, Newport. barry.atkins@newport.ac.uk

Monday, 8 September 2008

Space, the Final Bit

Sporous thoughts. Rushed too fast at the game and got up into space. I always wondered how a game-that-was-4-games would play, and I guess my initial instinct that it would alienate almost everyone at least somewhere along the line was right, at least in the very limited sample of one that I have to hand. In converstion (ie, I have never checked the reference) I would evoke Stephen Hawking and his publisher's (?)injunction that he remove as many equations as possible from A Brief History of Time because his audience would halve each time one appeared. I kind of thought that the same would be true of a shift in gameplay control or focus, and I do have radically different responses to each of the parts so far. Cell level is pretty and relaxing, but feels fairly pointless to me, although my 7 year old daughter is a fan. Next stage was interesting enough as I boogied and waggled my butt to get through without getting violent once (and it was fun to play through with the junior game critic that is my daughter). The Civilised stage was a pushover as I tankrushed the planet, but with religous texts blaring from loudspeakers on my Converto-Wagon. Somehow I have gone interstellar as an evangelical godsquad herbivore, which is certainly playing against type. I'll see if I can dig up some screenshots and add in a while, but I am aware that I rushed the design side, which is where the real glory of the tools rest. Having helped aformentioned daughter (who, come to think about it is perhaps slightly overexposed to games) in MySims for the Wii it was all very familliar, but slightly more adult. Closer to Duplo than Mechano, and a long way from Maya, Max, or even SketchUp, but interesting enough to twiddle with if I wasn't being such a gamer in a hurry all the time. Hummm. More thought required.

Saturday, 6 September 2008

TR: Underworld

Ah, Lara. I continue to have an emotional attachment to the woman. If it wasn't for her I would still be a lecturer in English Literature...

Anyway, there is intelligent and considered commentary on the next Tomb Raider up on Gamasutra. This kind of developer conversation, that is featured a lot on Gamsutra, makes me think the future is not quite as bleak for games as I am sometimes given to think in the small hours when I look up at the now-no-longer-next gen games I have on the shelf and decide to boot something retro on the Wii or PSN.

Back now to Spore and the nagging feeling that I am kind of missing the point. I seem to have created a race of Jar Jar Binks-alikes, and somehow don't have the energy to do anything more than drive them to extinction. I remember when I got The Movies I sinned by accessing a cheat code so that I could go straight to making films, and feel I might have done something similar (although sans cheats) by rushing my species to the point of the game I am most interested in, rather than giving it the attention it probably deserves.

Not sure I particularly want to go back to the primordial soup, however, but we'll see.

Anyway, there is intelligent and considered commentary on the next Tomb Raider up on Gamasutra. This kind of developer conversation, that is featured a lot on Gamsutra, makes me think the future is not quite as bleak for games as I am sometimes given to think in the small hours when I look up at the now-no-longer-next gen games I have on the shelf and decide to boot something retro on the Wii or PSN.

Back now to Spore and the nagging feeling that I am kind of missing the point. I seem to have created a race of Jar Jar Binks-alikes, and somehow don't have the energy to do anything more than drive them to extinction. I remember when I got The Movies I sinned by accessing a cheat code so that I could go straight to making films, and feel I might have done something similar (although sans cheats) by rushing my species to the point of the game I am most interested in, rather than giving it the attention it probably deserves.

Not sure I particularly want to go back to the primordial soup, however, but we'll see.

Tuesday, 19 August 2008

More Pictures

Dual Core

And now the other half of the thing. A complete reskin of The Lovers. Exactly the same game, but skinned differently. If I were a Social Scientist and knew anything about questionnaires etc. I would have some questions to ask about whether the experience of what people call gameplay differs substantially as a result. Mind you, you have to get a compelling game together first.

Dual Core at YoYo

Both games/versions should be sitting in the Box.net widget off to the right as well.

Thursday, 14 August 2008

Reboot